What They Copied

Jony Ive built the iPhone. The car industry copied the screen. The Ferrari Luce is Ive trying to teach them again.

Jony Ive created the iPhone to be the everything device. It’s a camera and a text messenger and a game console and a movie player and a web browser and a thousand other things, and it has a touchscreen because it has to — because a physical keyboard can’t be a shutter button, and a number pad can’t be a search bar. The touchscreen was the solution to a specific problem: how do you build one device that does everything?

Then carmakers looked at a product that sold billions of units and said, we should put one of those in the dashboard. But they took the wrong lesson. Your car isn’t supposed to do everything. It’s supposed to be a car. You need to adjust the temperature, change the volume, turn on the heated seats and keep your eyes on the road. These are not problems that require a general-purpose interface. They are problems that have been solved for more than a century — by knobs and buttons and switches — and the industry unresolved them in a decade.

Ive knows this. “The reason we developed touch — the big idea was to develop a general-purpose interface that could be a calculator, that could be a typewriter, could be a camera, rather than having physical buttons,” he told me. “To use touch in a car is something I would never dream of doing, because it requires that you look at what you’re doing.”

He paused. “Touch was seen as almost like fashion. It was the most current technology. ‘We need a bit of touch.’ And, ‘You know what we’re going to do next year? We’re going to have an even bigger one.’ That’s just the wrong technology to be the primary interface.”

So the man who inadvertently ruined car interiors is back to fix them. And on a Ferrari, no less — the new Luce.

The event was held at the Transamerica Pyramid in San Francisco. Ferrari CEO Benedetto Vigna explained the choice: the building was constructed by A.P. Giannini, the Italian-American founder of Bank of America; LoveFrom’s studio is nearby; and the architect tapered the building’s shape specifically so that light could reach the streets below. “Luce,” the newly revealed name of Ferrari’s first electric vehicle, means “light” in Italian. If you thought the symbolism was accidental, you haven’t spent much time with Italians. On the last night, they illuminated the Pyramid’s spire in red — for Ferrari, for light, for the start of something.

This was the second of three phased reveals for Ferrari’s first fully electric car. The first, in Maranello last October, covered the underlying technology — battery, motors, platform. This one was the interior and interface. The exterior comes in May, in Italy. Ferrari is spacing these out deliberately, and it’s the right call. There is so much going on in the Luce’s cabin that stuffing it into a single launch alongside the exterior would guarantee most of it gets lost.

They didn’t call the car “Elettrica.” Vigna told us he’d had a journalist suggest as much that very morning. Too simple, he said. Because the argument Ferrari is making — and it’s the same argument Ive, Marc Newson and LoveFrom are making — is that this is a Ferrari that happens to be electric, not an electric car that happens to be a Ferrari. The powertrain is a feature, not the identity. As Ferrari’s Chief Design Officer Flavio Manzoni put it: “Electric is a feature of this Ferrari Luce. This is why electric would have been a wrong name.”

Over dinner, I asked whether they’d approach a diesel powertrain — or any other technology — the same way. The answer was essentially yes: as long as it achieves the goal, whether that’s getting across the finish line first or enhancing the driving experience, the technology itself is irrelevant. You don’t do tech for tech’s sake.

The collaboration between Ferrari and LoveFrom has a backstory that borders on poetic. The idea to work with Ive and Newson predates Vigna’s arrival as CEO. In 2021, when Vigna was interviewing with Ferrari chairman John Elkann, he was asked: “What do you think if we work with LoveFrom?” Vigna didn’t even recognize the name — the company had barely started. “LoveFrom?” he asked. “Jony Ive and Marc Newson.” “Oh, okay.”

But Vigna’s endorsement wasn’t a guess. He’s a physicist by training, and in a previous career, his team developed the three-axis accelerometer that ended up inside the iPhone. He’d worked, if not directly with Ive, then on the same product — “designing a beautiful product that we use nowadays every day,” as he put it. So the man who built the iPhone’s guts and the man who designed the iPhone’s face are now collaborating on a car interior that rejects the damage the iPhone inadvertently did to automobiles.

Australian Marc Newson is one of the only industrial designers in the world who could give the British Ive a challenge — it’s perhaps little surprise that they’ve been best friends for 30 years. “As I’ve gotten older and grumpier, who I work with is more important than what I work on,” Ive said. He brought Newson into Apple in 2014 to work on the Apple Watch.

When Ive left in 2019, the two created LoveFrom, which now employs about 60 designers in San Francisco and London — “the best of the best of the best designers I have ever been lucky enough to meet,” Ive said, “and also the kindest. That’s part of my grumpy belligerence now — I’m done working with assholes.” The team includes typographers, industrial designers, mechanical engineers, UI designers and filmmakers, working across disciplines in a way that is almost unheard of in the automotive world, where departmental silos define the product.

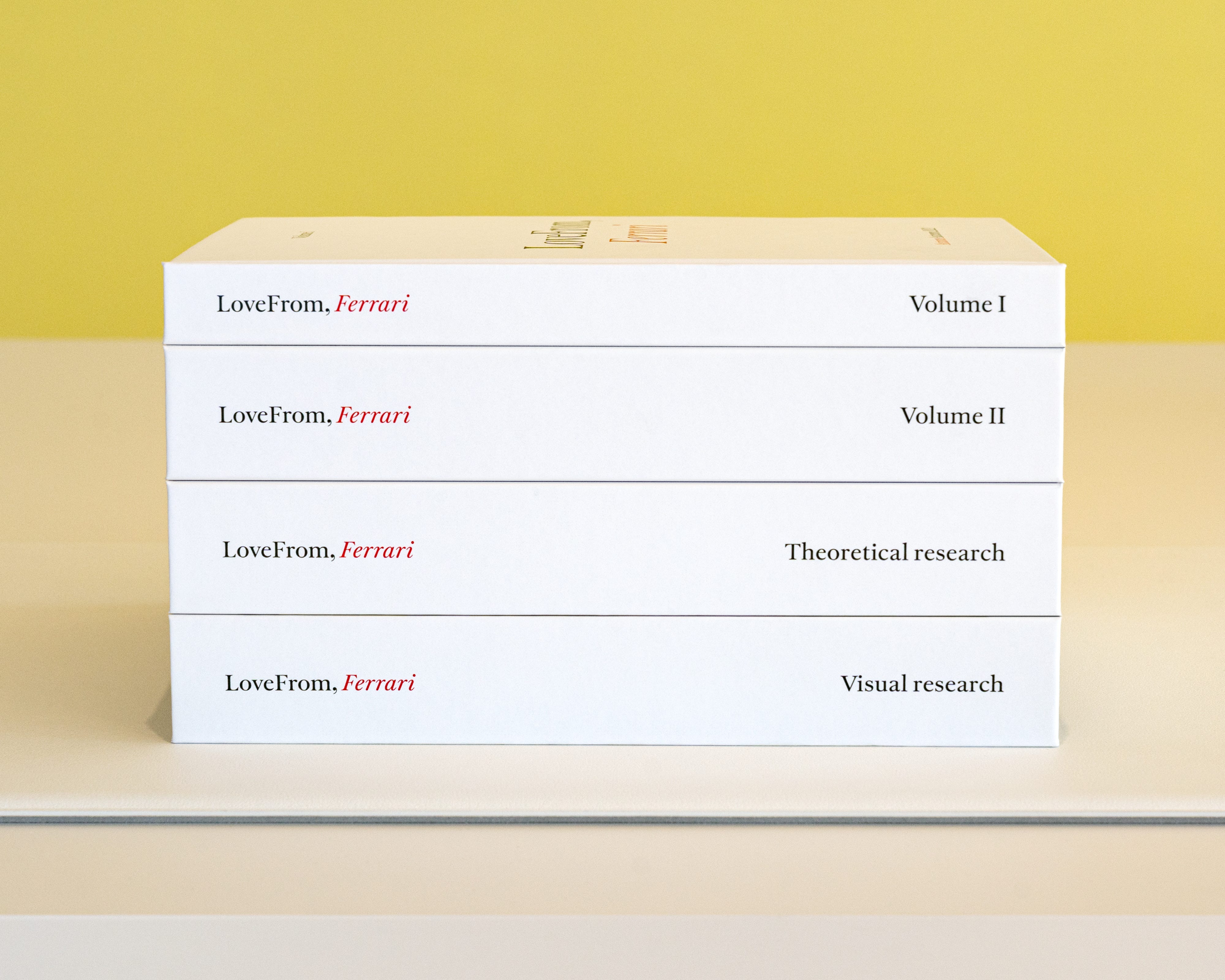

Before LoveFrom drew a single line, they spent six months on research. They presented Ferrari with four books — substantial, rigorous volumes printed in both Italian and English, left page and right page, covering philosophy, design history, the cultural significance of Ferrari within Italy, the relationship between human attention and physical interaction. These weren’t mood boards. They were arguments — about why certain assumptions held, why others didn’t and what first principles should govern the design of a car interior in 2026.

Vigna still reads them. “When you write, you’re forcing yourself to explain better your thoughts, and you’re forcing the reader to go through the details,” he said. “Those books were forcing us to review why something was done a certain way. I remember the discussion we had on the position of the spokes of the steering wheel — why that angle? And this was an occasion for us to go talk with the test drivers.”

Manzoni, Ferrari’s chief design officer, gave LoveFrom full autonomy for those first months. When they came back six months after the first handshake, “their proposal was completely cohesive — exterior, interior, user experience... [and] very disruptive.”

Asked during the afternoon Q&A how much the final design had changed from LoveFrom’s initial proposal, the answer from both Ive and Newson was — barely at all. Manzoni said that if you saw their first models and the production components side by side, “you could be surprised about the similarity.” Any changes were proportions and ergonomic refinements, not fundamental rethinking.

I asked whether the fact that nothing changed meant they’d played it too safe. “Great question,” Ive said — and then didn’t answer. Newson stepped in and explained that the first eight or nine months was intense research, the design period was relatively short, and the last two and a half years — more than half the five-year project — was just getting it built. Getting it made.

The automotive industry works the other way around. Car companies sketch first, research later, iterate endlessly, compromise constantly. Every department fights for its priorities. The interior gets designed by one team, the software by another, the exterior by a third. The result is exactly what you’d expect from that process.

LoveFrom’s process inverts that entirely. Research drives the thinking. The thinking drives the shapes. If you do the research right, the design becomes almost self-evident. The obvious answers stay obvious because no one is in the room arguing them away. “I just love learning more than I love being right,” Ive said. “At the end of a project, there’s two products — there’s what you designed and what you learn.”

This article is sponsored by Nokian Tires. I ran their winter tires on my own cars for years before they ever sent me free ones. The Finnish have been making specialized winter tires since 1936 — they know cold weather.

If you’re curious about tire choices for your vehicle, email me and I’m happy to help.

The Luce isn’t a car Ive has been designing in his head for 20 years. The concepts that drive it didn’t exist 20 years ago. Back then, “the concepts were so very different,” he told me. “What’s happened is people have become more and more disconnected from the physical world and more and more isolated.”

This car is a response to now — to the specific condition of 2026, where we’re drowning in screens and the one activity that used to force us into physical presence has been colonized by the same digital abstraction as everything else.

“I think we personally feel that we’ve become more and more isolated in our digital worlds from the physical world,” he said. “I think it’s one of the reasons we probably all love driving. And I think — rebellion is far too strong a word — but I think there is a growing desire to not be isolated, disconnected, whether it’s from each other or the real physical world.”

The Luce isn’t a nostalgia trip. It’s not a retro reaction against technology. It’s an argument that the things we touch and feel and move with our hands are essential to being human — and a car, a thing that moves your body through physical space, should connect you to the physical world, not insulate you from it.

It matters that this is a Ferrari and not some other car. “Of course, if we were designing this for somebody else, it would be very different,” Ive said, “but you want to drive your Ferrari and enjoy driving it.” The physicality, the paddle shifters, the manettino, the steering-column binnacle — all of it is specific to Ferrari’s mission and its drivers. LoveFrom didn’t impose an aesthetic on a car company. They spent years understanding what Ferrari specifically needed.

The interior components were displayed upstairs on individual plinths, like objects in a design museum. That wasn’t just for dramatic effect. Marc Newson explained: “Each one of these objects is, in itself, incredibly beautiful. I’d love to have any of these things at home.”

If you take a traditional automotive interior component out of the car and set it on a table, it looks like an orphaned piece of a larger machine — because it is. It was designed to fill a space defined by other constraints, sculpted to fit surfaces that were themselves sculpted for packaging or cost. Ive put it bluntly: “If you take, traditionally, an automotive part out of context, it’s a very odd shape, because generally you define a set of surfaces, and then you sort of say, ‘well, this is where the speaker goes.’”

LoveFrom’s approach was the opposite. They designed each component as a self-contained product — “as if they were a camera or a watch,” Ive said — and then integrated them into the cabin. Newson called it a project of a thousand products. The steering wheel is one product. The binnacle is another. The control panel, the central console, the shifter, the key, the vents — each one designed to be complete and beautiful in isolation, assembled into a coherent whole. Everything designed to look as beautiful from the back as it does from the front.

LoveFrom designed the interior and exterior simultaneously — not one wrapped around the other, as is standard in the industry. They designed the physical hardware and the digital software as one team. Jeremy Bataillon from LoveFrom explained: “We have industrial designers and we have UI designers, and we work together as one team. Usually it’s separate teams that do that work, and therefore they cannot come up with those ideas.”

The result is an interface where the physical and digital actually talk to each other. Press a physical button on the steering wheel and the display behind it responds — not with a static icon, but with a dynamic graphic that expands to show you more information. Turn a dial and the screen tracks your input in real time. The hardware and the software weren’t developed in parallel and bolted together at the end. They came from the same team, at the same time, as one thing.

When Ive walked us through the interior, he started with the organizational logic. “This is driving,” he said, gesturing at the steering wheel and binnacle. “Every other element augments the driving experience, but the focus of the steering wheel and this binnacle is very clearly about driving.” Then the rules: “This is output. This is input. Because these controls are mechanical.”

That clarity of organization sounds obvious. It isn’t. Walk up to any modern luxury car and try to figure out, from a standing start, how to adjust the climate. You’ll be three menus deep in a touchscreen within seconds, and you still might not have found it. In the Luce, Ive said, “When you look at this, you’re not wondering — how many layers deep am I going to have to go to find something to make my bottom warm?”

I asked whether there was ever a discussion about making the physical controls flexible — a button that could be a heated seat toggle or a drive mode selector, depending on context. Ive’s answer was instant and direct: “And you would have hated that.”

He didn’t need research to know that was a terrible idea. Everyone knows it’s a terrible idea. And yet the industry keeps doing it — multi-function touch surfaces, haptic zones that change depending on the menu, capacitive sliders that control different things in different modes. All of it requiring you to look at what you’re touching instead of keeping your eyes where they belong.

“I think we’re all really proud that when you look at the central console, it’s — ‘oh, I know how to turn on a seat heater. I know how...’” He trailed off, almost incredulous. “You just can’t do that anywhere anymore.”

“If you can’t use something, it’s ugly,” Ive said. “There’s a deep, deep ugliness to something that just drives you crazy.”

“Beauty takes many forms, doesn’t it?” he asked, almost wistfully.

This is Ive’s design philosophy compressed into a single thought. Beauty and function aren’t competing priorities that need to be balanced. They’re the same thing. A gorgeous touchscreen that forces you to take your eyes off the road at 80 miles per hour isn’t beautiful. It’s ugly. A palm rest that gives your hand a datum point so your fingers can find every control without looking — that’s beautiful. A toggle switch with precisely tuned mechanical feedback that tells your fingertip exactly what it did — that’s beautiful. The ugliness is the dysfunction. The beauty is the solution.

Formula One drivers know this. Their steering wheels have dedicated switches for the critical functions and deeper digital menus for mid-race strategy adjustments. Fighter pilots know it — the controls you reach for in a critical phase of flight get dedicated, physical hardware. You don’t bury the landing gear in a submenu.

Ive went further than design critique. Almost as an aside, he mentioned “the number of people dying because of dumb interfaces.” He said it like it was obvious. It is obvious. And it’s maybe the most damning thing a designer of his stature can say about the rest of the industry — that the way cars work right now isn’t just annoying or ugly. It’s killing people.

The steering wheel tells you everything about the philosophy in a single glance. It’s a three-spoke design — heritage Ferrari, traced back to the Nardi wheels of the 1950s and 60s — but in exposed, anodized aluminum. Most modern steering wheels have a metal structure underneath, hidden behind plastic or leather or both. Here, the aluminum is the point. You see it. You feel it. It’s cold when you first touch it on a winter morning, because it’s metal, because it’s real.

The heritage wasn’t an afterthought. Newson noted that they spent significant time with Piero Ferrari — Enzo’s only living son, now 80 — who “was instrumental in reinforcing some of these really important design cues that have been with Ferrari since the very beginning, like the three-spoke steering wheel.” Piero was keen on the purity of the design, deeply supportive of LoveFrom’s approach. Ive, who owns a 250 Europa — a roughly $2 million car and a serious machine, not a casual collector’s trophy — said: “We know the brand well. We love the brand. We drive it. People could see our deference and respect and our determination to really try to make a contribution.”

The wheel is made from 19 CNC-machined parts in 100% recycled aluminum alloy, developed specifically for this car. The monolithic hub alone takes more than four hours to machine from a solid billet. The spokes are impossibly thin — the Ferrari team told me there’s nothing this compact on the market. It weighs 400 grams less than a standard steering wheel. The controls are organized into two analog modules inspired by Formula One, and every button went through more than 20 evaluation tests with Ferrari’s test drivers.

Those buttons. They’re glass and aluminum, no plastic. Each one feels different under your fingers — deliberately, so you can identify them by touch without looking down. There are toggle switches that snap with a crisp mechanical action (magnets pulling them back, not springs — very F1) and rotary dials with defined detents. The manettino — Ferrari’s iconic drive mode selector — gets a new electronic version on one spoke; the classic suspension manettino sits on the other.

And the paddle shifters. On most electric cars, there are no paddles — there’s nothing to shift. Some, like the Hyundai Ioniq 5 N, have tried to recreate the sensation of shifting with a simulated transmission that actually slows the car down to mimic the feel of an internal combustion engine. Ferrari would never slow a car down for the sake of theater. Instead, the paddles do something real: one controls the intensity of regenerative braking, the other adjusts the aggressiveness of the motor’s torque delivery. I want more regen going into a corner. I want more torque coming out. That’s what these do. Ferrari told me the idea originated early in the process — they wanted variable torque and regen settings to keep the driver engaged, as in any other Ferrari, and the paddles were right there waiting. It’s not nostalgia for a gearbox. It’s a new function that happens to live exactly where a Ferrari driver’s hands already know to reach.

Then there’s the turn signal. It’s a two-stage button — press lightly and you get the three-blink lane change; press fully and the signal stays on. You know by feel which one you’ve done. It’s a tiny detail, but it’s the kind of thing that tells you someone actually thought about what your fingers are doing while your eyes are on the road. Every button on this wheel has that quality. Nothing feels the same as the thing next to it.

The binnacle — the instrument cluster — is where the most technically ambitious ideas live. It’s attached to the steering column, which means it moves with the wheel when you adjust the driving position. This is a first for Ferrari, and it solves a problem that Ive finds absurd about conventional cars: “You have a driving environment, and what do you do to adjust the fit? You slide a chair backwards and forwards, which is quite crude, really.”

The binnacle itself is a layered construction of two overlapping Samsung OLED displays. The top display has three large cutouts — a world first, cutting holes in OLED panels at this scale — that reveal a second display behind it. Each cutout is covered by a convex glass lens, and as you move your head, you get parallax. Real parallax, the kind that comes from actual physical depth between layers. “If you want to avoid parallax,” Ive said, “just play computer games.”

And then, rising through the space between the displays: a physical needle. An actual, mechanical needle, illuminated from beneath by 15 LEDs injecting light through a fiber-optic guide, rotating with less than a millimeter of clearance from the display surfaces on either side. It reads your speed while the digital display behind it provides context. I don’t know what to call it. It’s not analog and it’s not digital. It’s something else.

Samsung Display’s VP Shawn Kim explained that the free-form OLED panels were only possible because of the technology’s inherently simple structure — no backlight assembly, no rigid layers — meaning they could cut them into shapes that would be impossible with LCD. When Ferrari first showed Samsung the design, Kim said it was challenging from a manufacturing perspective. “But we loved the enthusiasm of the engineering. We just took a look at how to make it happen.”

Andrea Binotti, Ferrari’s head of development, told me the double-screen binnacle was the element that surprised him most — the thing he’d never seen before, the idea that came from LoveFrom and that Ferrari’s engineers had to figure out how to build. Maybe that’s the answer to the question of whether Ive and Newson pushed far enough: the ideas didn’t change because they were the right ones all along. And getting Samsung to cut holes in OLED panels and getting a mechanical needle to spin between two displays with sub-millimeter clearance — that took two and a half years. Their design stretched the limits of possibility and got executed anyway.

The control panel — the central display, such as it is — sits on a ball-and-socket joint. You can grab it and swing it toward the driver or the passenger. But the key detail isn’t the movement. It’s the handle.

“It’s common sense, but something that’s bizarrely ignored,” Ive said. “It’s very hard to hold your hand out if you’re moving and find a button.” The handle serves primarily as a palm rest — a physical datum point. With your palm resting on it, every switch and dial on the panel is within reach, and you know where each one is without looking. It’s not complicated. It’s not new technology. Someone just had to actually think about what it’s like to reach for a button while a car is moving.

This is Ferrari’s own interface — not Apple CarPlay, not a third-party system. (It does support both wireless CarPlay and wireless Android Auto, but the native UI is entirely bespoke.) Binotti confirmed they built the UI layer themselves with LoveFrom’s expertise. “We have full control,” he said. “We didn’t compromise with anything.”

And then there’s the software philosophy, which might be the most radical thing about the whole car. Binotti said: “We are not used as Ferrari to have, let’s say, update software many times during their lifetime. That’s the masterpiece — it’s done.” It’s not that Ferrari can’t update its cars. It’s that they intend to ship a finished product. Every other automaker is spending billions trying to build update infrastructure they can barely manage; Ferrari is simply choosing not to play that game.

There’s a longevity argument here too. Ferrari’s current cars have intentionally minimal connectivity — one-way communication from the car to Ferrari’s app, sending basic information like tire pressures, but no remote unlocking, no location tracking, no cloud dependency. The Luce will have a new app and likely a new connectivity philosophy, but the underlying instinct is the same. Part of it is privacy, a real concern for their ultra-high-net-worth clientele. But part of it is durability. Ferrari has a division called Classiche that maintains and restores every Ferrari ever made — they have the original drawings for every part on every car, and can build replacements to original specifications. They’re already working to ensure the Luce can be maintained and restored decades from now, the same way they service cars from the 1950s today. Connectivity ages out. Aluminum and glass and precision engineering do not.

Embedded in the control panel is what Ferrari calls the multigraph — a precision instrument with three independent motors, three anodized aluminum hands, and a Corning glass crystal. Press a button and it transitions from clock to chronograph. Reach above your head and pull the launch control handle — mounted on the roof like an eject lever, gloriously dramatic — and it switches again, the hands sweeping to new positions. The engineering team told me the mechanism had to be maintenance-free and reliable over the life of the car. I asked if watchmakers were involved. They didn’t deny it.

The key might be my favorite part of the whole thing.

It’s a slab of Corning Fusion5 glass with an E Ink display — a first in automotive. In your pocket, it’s yellow. Ferrari yellow. It doesn’t drain power because E Ink is bistable: it only uses energy when changing states. When you get into the car, a magnet in the center console guides the key into its dock. Press it down, and the yellow fades to black as the key integrates with the glass surface of the console. Simultaneously, the binnacle and control panel light up — and the white glass of the shifter turns yellow, as if the car is saying: okay, now touch this part. The car comes alive in sequence, each element handing off to the next.

Ive called this “theater,” and he’s right. Electric cars fundamentally lack the ritual of starting up. There’s no engine turning over, no rumble settling into an idle, no mechanical systems awakening. The Luce’s key ceremony isn’t trying to fake that — it’s creating a new version of it, native to what this car is. A different theater from a Ferrari V12, but Ferrari theater nonetheless. “When you see it holistically, it’s not boom, boom, boom,” Ive said. “It’s — oh, that’s nice. Somebody actually thought about that process.”

A few years ago, I had a 488 for a week. Beautiful car. But there was no place to put the key. Ferrari’s solution was a tiny velvet-lined spot in the cupholder, and I remember thinking: someone didn’t think about where I’m going to put my key. With the Luce, someone did. It has a home, it has a ritual, and when you’re done driving, the black fades back to yellow as the key releases. Binotti told me they spent a lot of time thinking about the fact that this sense of ceremony was missing from most electric cars — and most combustion Ferraris, for that matter.

What runs through all of this — the steering wheel, the binnacle, the controls, the key — is what Ive calls “truthful materials.” The aluminum is aluminum. The glass is glass. Nothing is pretending to be something it’s not. And the entire interior is essentially just these two materials, plus leather where your body contacts the car — the steering wheel rim, the seats, the armrests. This is far from the first time Ive has crafted things from aluminum and glass. The iPhone, the MacBooks, the Apple Watch, the Apple Stores he designed with Norman Foster — his entire career has been spent understanding how these materials machine, how they anodize, how they age, how light moves through and across them. (The original iPhone even had a plastic back; Apple spent years iterating toward the all-glass-and-aluminum object it eventually became.) He knows what these materials can do. That’s a big part of why the execution here is at a level nobody in the car industry has come close to.

Corning, the company that makes Gorilla Glass for your phone (also at the behest of Steve Jobs, incidentally — you start to see the patterns), developed the glass components for the Luce using their Fusion5 formulation, which is stronger in flexure than sapphire and more scratch-resistant than conventional glass. Corning’s VP of automotive glass solutions, Mike Kunigonis, explained why glass and not polycarbonate: imagine you’re on a beach, he said, and your kid picks up a piece of sea glass — smooth, polished by the waves, light passing through it. You put it in your pocket, take it home, set it on your desk. Now imagine they pick up a piece of plastic. You tell them to throw it away. “Glass has this strong emotional connection,” he said. That connection is why there are more than 40 glass parts in the Luce’s interior. The typical car has one or two, maybe three.

Kunigonis’s team needed seven new process innovations just to meet LoveFrom’s specifications. The shifter alone required Corning to laser-drill more than 13,000 holes in the glass surface — each one about 40 microns, a third the width of a human hair — so that light could pass through uniformly, allowing the shifter to glow when the car is on and appear dark when it’s off. They tested the glass components, in some cases, to an equivalent lifetime of 50 years without failure.

And the vents — I know, nobody writes about vents. But lean in and listen to the Luce’s air vents. The precision of the movement, the quiet mechanical click of the louvers as they pivot. You don’t need an instruction manual. You open it, you aim it, you close it. “I would defy anybody to use this and just be nonplussed and walk away,” Ive said. He’s not wrong. You don’t need to go through three layers of a touch interface to direct the airflow. You just move it. With your hand. Like a person.

Near the end of the day, I asked Ive what he’d want the rest of the industry to take away from this. Newson jumped in first: “Nothing. We want it all to ourselves.” Everyone laughed.

Then Ive got serious. “What would be lovely would be for the thinking to be talked about, not the shapes,” he said. “We all know that there’s a frustration — our observations are hardly earth-shattering, in terms of the functional problems, or the number of people dying because of dumb interfaces. What we don’t like is when work is understood in terms of styling. Of course, the ultimate manifestation of an idea is form. So of course we’re obsessed with that. But the underlying thinking, I think, is really important. I think it’s nice when that becomes a discussion.”

The thing that drives him crazy, he said, “is this belief that doing something new is valuable. New is really easy. We could all sit down and do something new in half an hour. If difference and new is because it’s better — I think that’s what we would love.”

If you’ve ever watched Jony Ive in an Apple new product video, you see that they think through every step. It makes sense when a billion people are going to use the thing. The Ferrari Luce might sell a few thousand units a year. But every piece — every toggle, every thread on every vent louver — was created as if a billion people were going to touch it. That’s not because Ferrari buyers deserve more care than the rest of us. It’s because Ive doesn’t design to a volume; he designs to a standard: would this be good enough if everyone on earth had to use it? The shapes might be Ferrari, but the thinking is universal.

When I listen to my recording of our group Q&A session, I can hear him struggle to express the idea that’s perfectly formed in his head. The half-finished sentences, the trailing off, the idea circling three times before he lands on it: “What would be lovely would be for the thinking to be talked about, not the shapes.” He’s not simply being a polite Englishman. He’s lonely. He made the iPhone, and an entire industry looked at it and learned the wrong thing. Not the wrong lesson — the wrong thing. The lesson was: ask what problem you’re solving, then build the solution that solves it. What they took was: put a touchscreen in the dashboard. And people are dying for it.

Now he’s trying again, putting the thinking directly into a car, in a context where you can’t miss it — physical controls, dedicated buttons, a palm rest so your hand knows where it is while your eyes stay on the road. He’d make this car whether anyone in the industry learned from it or not. That’s the job: to make the beautiful thing. And to Ive, beauty and function are the same word. But, in both his words and his design, you can hear him pleading — wistfully, almost to himself — for someone, anyone, to look past the aluminum and the glass and see why.